Intelligence Hub

Economic Briefing October 2025

Introduction

Economic Context Ahead of the November Budget

Next month, the Chancellor will deliver the Autumn Budget against a particularly challenging economic backdrop. The outlook for living standards remains challenging, with many commentators noting that people increasingly feel disconnected from economic growth and that their living standards are deteriorating.

Household disposable incomes have yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels, with many families struggling to make ends meet. Recent economic data and forecasts suggest that worse impacts on household finances may still lie ahead. Recent data also points to rising levels of in-work poverty and growing regional disparities in income and opportunity.

However, it is not all bad news. There are some encouraging signs in the wider economy – a rare increase in productivity growth has been recorded, according to analysis by the Resolution Foundation. This offers a potential foundation for improving wages and long-term prosperity if the gains can be sustained and shared more broadly.

This briefing summarises the latest research on living standards and poverty in the UK and highlights the policy responses within GCR’s control that could help mitigate these challenges. These include targeted support for low-income households, investment in skills and sectoral strengths, as well as measures to support businesses that contribute to better living standards for employees and communities.

The recent awarding of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt reinforces these priorities. Their work demonstrates how knowledge accumulation and innovation underpin sustained economic growth and improved living standards. It underscores the importance of investing in science, technology, and skills, fostering openness to new ideas, and designing effective R&D policies that drive truly transformative innovation – lessons that closely align with GCR’s ambition to build a more productive and inclusive economy.

State of the UK and Scottish Economy

The latest macroeconomic data continues to show a mixed picture.

GDP

- The UK’s GDP grew by 0.2% in the three months to July 2025, a decrease from the 0.6% and 0.3% growth figures from the two previous three-on-three-month periods.

- For the first half of the year the UK was the fastest growing economy in the G7, however these periods of growth are anticipated to slow in the second half of the year and this is reflected through low business confidence. The Institute of Directors latest Economic Confidence Index fell to its lowest rating in Sep 25 since the Index began in 2016.

Labour Market

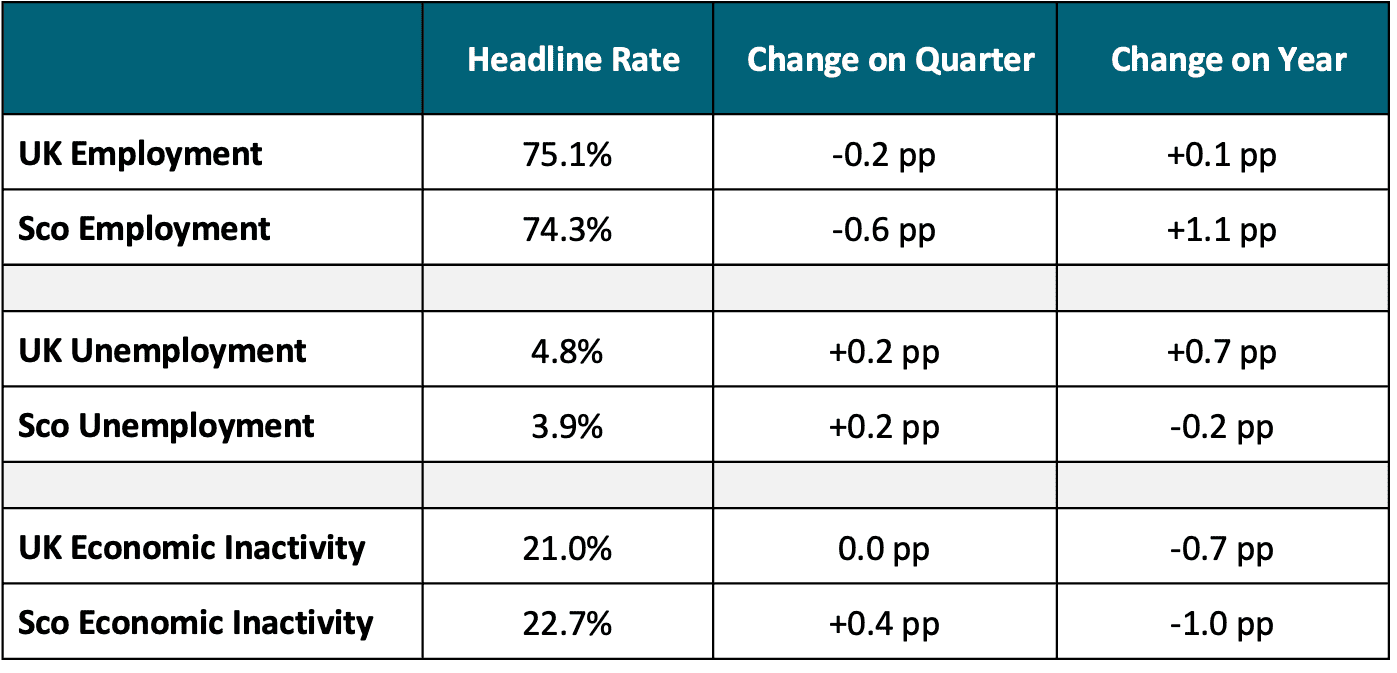

- The pessimism shown in the Economic Confidence Index aligns with a recent contraction of the UK and Scotland’s labour markets. Depending on how the Chancellor decides to meet her fiscal challenges, this may be exacerbated further after the Autumn Budget.

- Over the last quarter the employment rate decreased in both geographies, whilst unemployment and economy inactivity increased or remained the same. The latest quarter’s contraction has dampened but not fully diminished the labour market progress (UK and Scotland) since this time last year.

Chart 1: Labour market rates, Scotland and UK, June to August 2025

According to the IMF, the UK faces the worst G7 Inflation driven by profiteering.

- UK inflation has stayed at 3.8% in September.

- However, in its World Economic Outlook, the IMF predicted UK consumer prices would rise an annual 3.4 per cent this year and 2.5 per cent next, faster than other G7 countries.

- The root cause of ongoing inflationary pressure is still a contested topic amongst economists. According to the Guardian and other economic commentators, what the UK faces is profit inflation (Source: The Guardian). The Treasury takes the opposite view as it sees inflation as a result of rising import costs and wage pressures.

- The sharp rises of food prices are particularly concerning , as it disproportionately affects the poorest families. According to the industry, costs are increasing due to supply-side pressures such as regulations and the rise in the national living wage (source: FT).

Chart 2: CPI annual inflation rate, UK

Source: ONS, Guardian

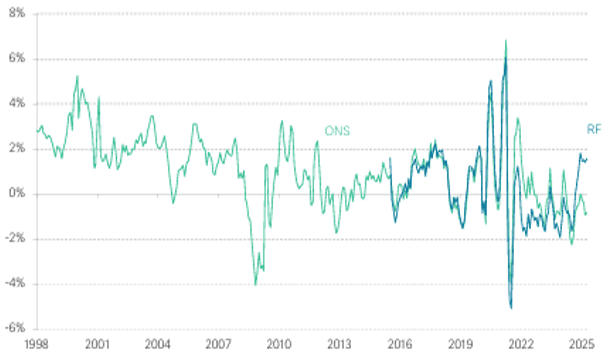

The UK has recorded a rare increase in productivity growth, according to the Resolution Foundation.

- The Resolution Foundation (RF) estimates output per hour worked rose 1.6% over past year. This is in contrast to the official estimate of 0.5%.

- The estimates are based on recently revised official estimates of GDP and figures for payroll employment drawn from tax records, rather than the official measures of hours worked drawn from the ONS’s labour force survey (the confidence problems of which have been discussed in previous briefings).

- Some economists have argued that the spike is due to recent job cuts in hospitality and retail, which were the hardest hit by April’s tax and minimum wage changes.

- There are signs of optimism too as improvements in high-value sectors such as IT and Professional Services were also noted.

- The RF warned that the short-term pick ups are not reflective of the UK’s long-term productivity problems which need to be addressed with pro-growth policies.

Chart 3: Annual productivity growth using official and RF measures of total hours worked, UK

Source: ‘’Trend Setters’’ Resolution Foundation

Living Standards

The UK risks further worsening of living standards

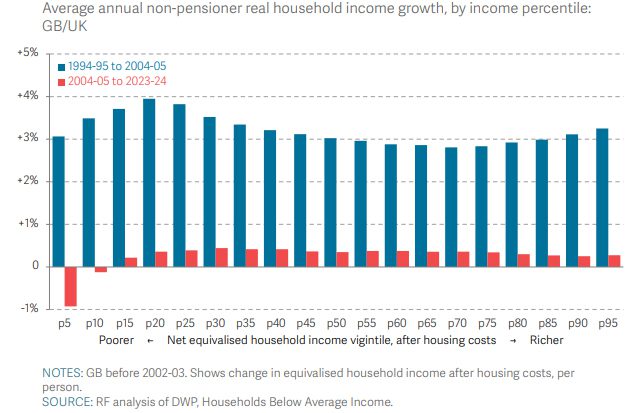

The Resolution Foundation has released a reflective report on the state of living standards in the UK over the past 20 years. It shows that income growth has stagnated to an unprecedented extent, especially in recent times.

The poorest have been disproportionately impacted

- While living standards have stagnated across all income groups, the poorest households have been hit hardest.

- Private renters have also experienced a sharp decline in living standards.

- Typical incomes have risen far more for pensioners than for working-age adults.

- The JRF projects that by 2029 average disposable incomes will be 1.3% lower than they are today – the sharpest drop in living standards since 1961.

Chart 4: Average annual non-pensioner real household income growth by earning percentile, UK

Source: The Resolution Foundation at 20 – Two decades of analysis, policy and change

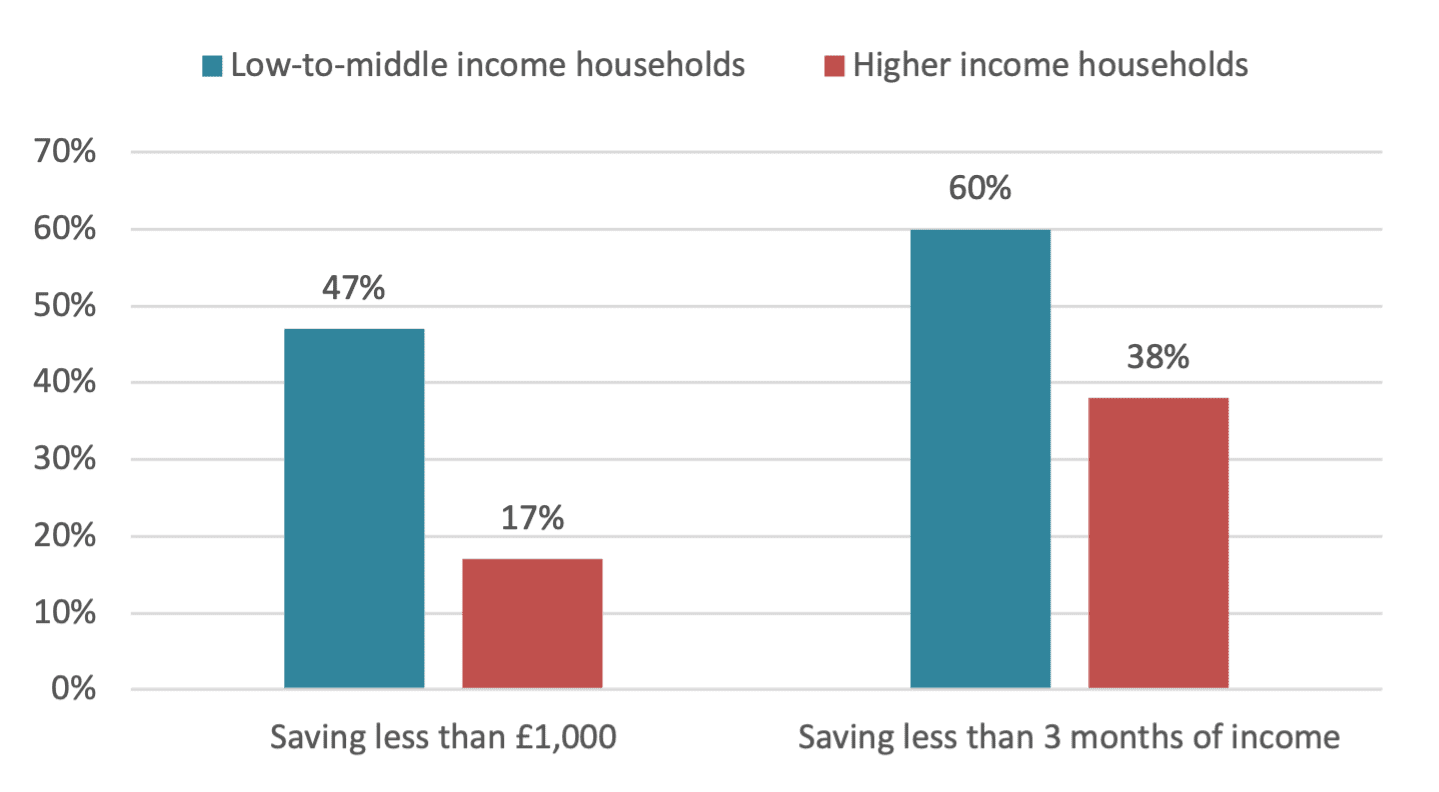

Financial Resilience of low-to-middle income households

Apart from income growth, living standards also depend on accrued debts and stocks of wealth. Savings and debt play a key role in the financial lives of low-to-middle income Britain.

- Low savings & financial vulnerability: Most working-age Britons have very limited liquid savings – two-thirds have less than three months’ income, and half of the poorest fifth have under £1,000 readily available – leaving many just a few paydays from financial trouble.

- Falling consumer debt but rising arrears: Since the financial crisis, unsecured debts have declined (especially among poorer households), but tighter credit and higher costs have led to a surge in arrears on essentials like rent, council tax, and utilities, with energy bill debts tripling since 2012.

- Policy priorities: A continued focus on living standards should be combined with targeted interventions on access to finance and support with the rising cost of essentials as well as debt-relief or advisory schemes.

Chart 5: Proportion of non-pensioner families with savings below a given threshold, by household income status: Great Britain, 2020-22

Source: ‘’Money on my mind’’, Unsung Britain Project, September 2025, Resolution Foundation

Poverty in Scotland

Poverty Trends

October marks Challenge Poverty Week – a time to raise awareness and call for meaningful action to end poverty.

- Poverty trends: Poverty in Scotland fell sharply from 24% in 1999–2002 to 18% in 2009–12, but has since risen to around 20% in 2021–24, though still lower than the rest of the UK due to lower housing costs and more social housing.

- Depth of poverty: The share of people in very deep poverty (below 40% of median income) increased steadily to 9% by 2019–22, representing almost half of all people in poverty, with only a brief recent decline that has not been sustained.

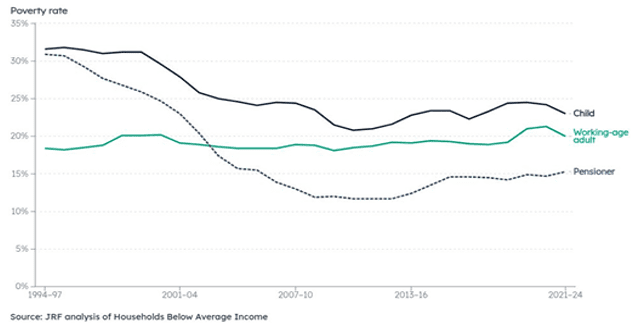

- Adults and pensioners: Working-age poverty increased from 18% in 1994–97 to 20% in 2021–24, peaking during the pandemic. Pensioner poverty dropped sharply from 31% to 12% (1994–97 to 2008–11) but has since risen to 15%.

- Children: Child poverty in Scotland fell until 2010–13, then rose from around 20% to 24% by 2018–21, remaining stable since. Scotland’s rate is now slightly lower than the UK average (30%), possibly due to the Scottish Child Payment, though its long-term impact remains to be seen.

Chart 6: Poverty rate for children, working-age adults and pensioners 1994-97 to 2021-24

Source: “Poverty in Scotland 2025”, October 2025, JRF

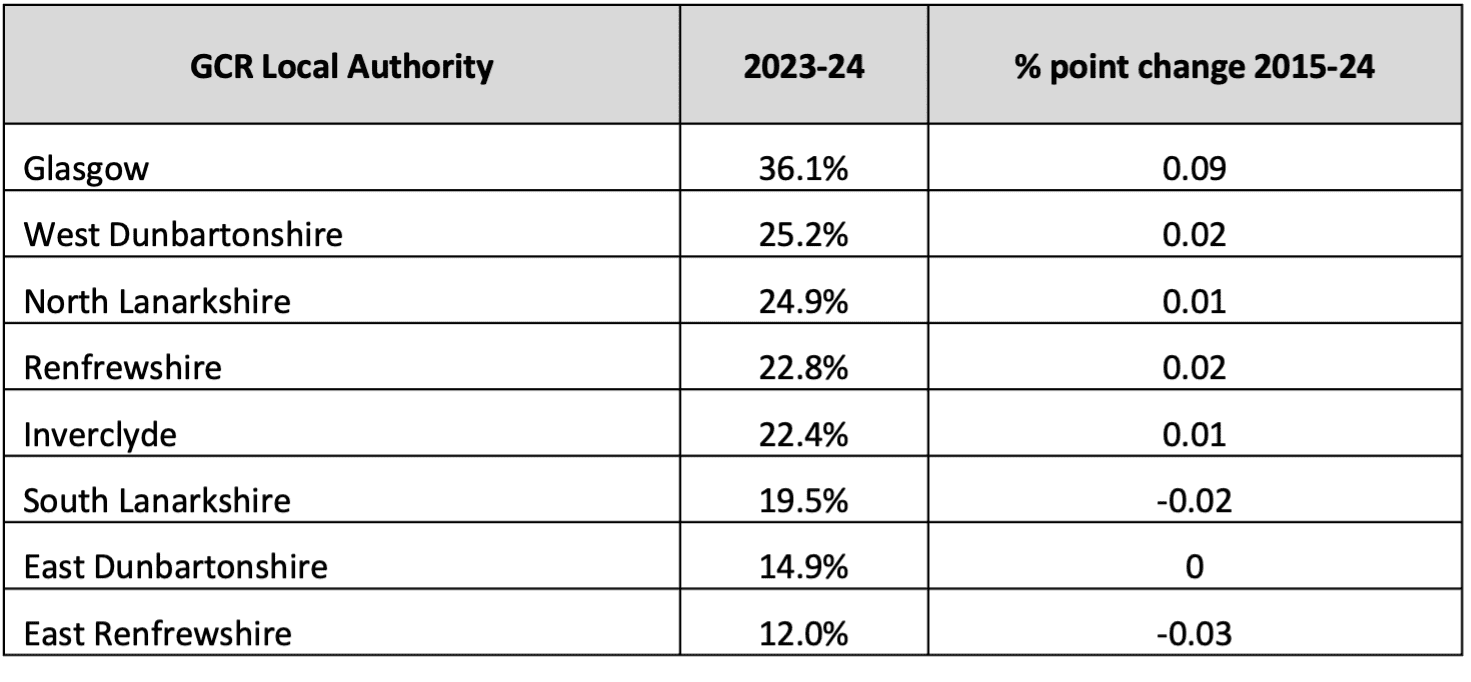

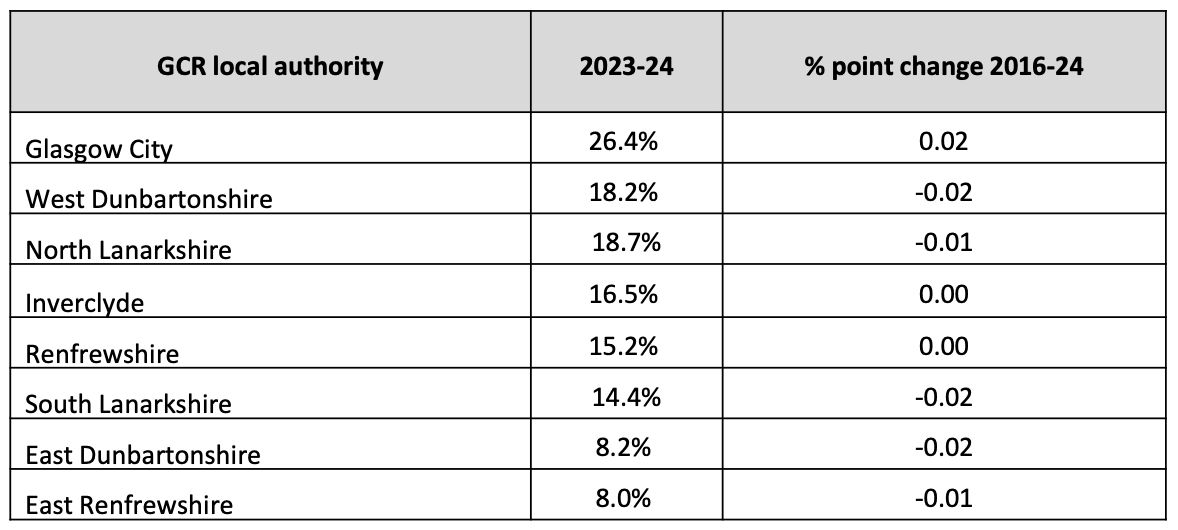

Local child poverty rates

Children in Scotland continue to be at a greater risk of poverty than the rest of the population.

- In 2023/24, nearly three-quarters of Scottish local authorities had at least one in five children living in poverty.

- Despite methodological differences between End Child Poverty (table 1) and the Scottish Government (table 2) both show that Glasgow City, West Dunbartonshire, and North Lanarkshire have the highest child poverty rates, while East Dunbartonshire and East Renfrewshire have the lowest.

- The Scottish Child Payment, introduced in 2021, has helped reduce child poverty overall, with 27 of 32 local authorities in Scotland seeing declines since its introduction. However, rates have risen in City of Edinburgh, Angus, Midlothian, Falkirk, Clackmannanshire and Glasgow City

Source: Poverty in Scotland 2025, JRF

Source: End Child Poverty, 2025

Source: Scottish Government

Policy Responses

A minimum income standard for the UK

The Minimum Income Standard (MIS) defines the level of income needed for everyone in the UK to achieve a socially acceptable standard of living, based on research.

Minimum Income Standard

- The Minimum Income Standard defines the income needed in the UK for a minimum socially acceptable standard of living, based on what the public considers necessary to participate in society.

- MIS covers essential needs – food, housing, clothing, transport, and participation in community life, but excludes luxuries.

- While not an official poverty line, most households below 60% of median income also fall below MIS, indicating they cannot reach an acceptable living standard.

- The MIS calculator can produce budget for over 100 household types.

Note: The Real Living Wage (independently calculated), uses the MIS as a foundation, whereas the government’s National Living Wage is a statutory minimum for those aged 21, based on recommendation from the Low Pay Commission (more here)

- The latest MIS report shows that in 2025 a single person needs £30,500 a year, and a couple with two children £74,000 jointly, to reach a minimum acceptable living standard.

- A full-time worker on the National Living Wage (£23,875) falls around £7,000 short of the income required for a single adult to meet this threshold.

- Despite rising employment, in-work poverty continues to grow: by 2022/23, 67.6% of working-age households below MIS included someone in paid work, up from 55.5% in 2008/09.

- The report finds that most low-to-middle income households still fall short of the MIS with only dual full-time working couples reaching it.

- In this context, policies that boost incomes for low-income households alongside addressing costs are essential to make sure that economic growth benefits the whole of society, enabling everyone to have a decent and dignified standard of living.

Trends show the importance of policy choices

More must be done to raise incomes from work. While GCR cannot influence social security policy, we can promote fair work and support businesses that pay decent wages.

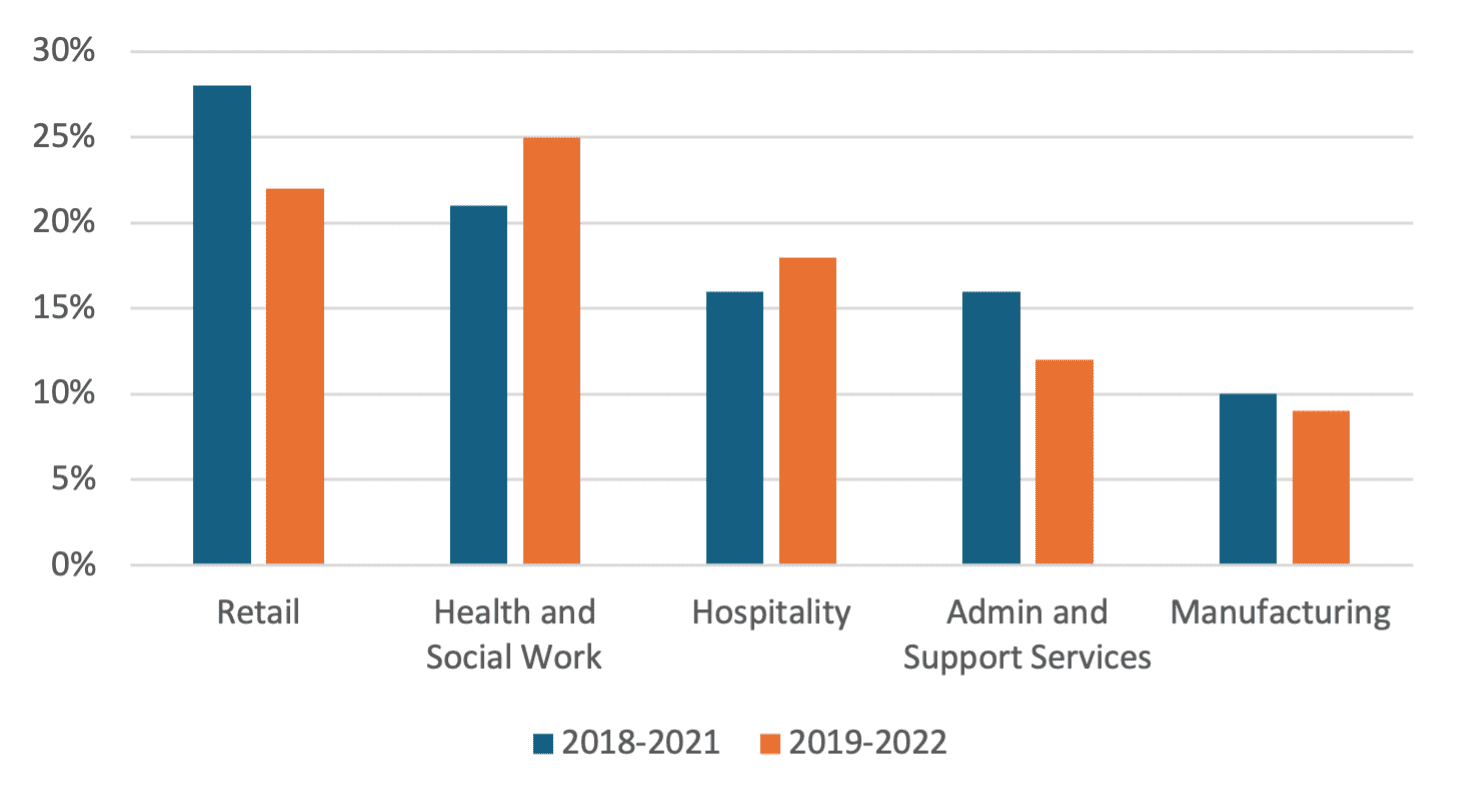

- In-work poverty: Work remains the biggest protector against poverty. However, the past decade has seen the collapse of earnings growth.

- Foundational Economy: As shown in the chart, the vast majority of people who live in poverty have someone in their family working in one of just five sectors. Although there have been improvements in some sectors, this is the part of our economy where low pay is concentrated.

- The Region has done a lot to support low-income workers through the Living Wage Campaign. More than 1,300 employers have now demonstrated commitment to the real living wage (RLW). Although this is positive, more is needed to ensure work can offer a good standard of living.

- Job Quality: The RLW alone can’t fix poor job quality, insecure hours, or instability. Policymakers must also focus on improving working conditions.

Chart 7: Proportion of people in in-work poverty where one or more people in their household work in the listed industry, 2018-21, 2019-22

Source: Analysis of the Resource Survey, stats sources from the JRF Family

What the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics teaches us about economic progress and living standards

In the context of falling living standards and renewed debates about how to drive economic growth across the UK, Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt have been awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics for their groundbreaking work on how knowledge accumulation and innovation sustain long-term economic growth and improve living standards.

Focusing on the transformative power of technological change, the laureates identified three essential prerequisites for sustained growth:

- The joint evolution of science and technology, ensuring that people understand why things work,

- Widespread mechanical and technical competence, and

- A society open to new and potentially disruptive ideas.

Their research raises fundamental questions about how seriously we take R&D and innovation within our broader economic strategy and how effectively our skills system and business support services nurture ideas and unlock the potential of talented people.

The laureates’ model also highlights the complexity of designing effective R&D policy. The optimal level of subsidy is not straightforward, as two competing mechanisms operate. On one hand, the economy can benefit from subsidising R&D when firms underinvest in innovations that may be quickly overtaken. On the other hand, subsidies can sometimes encourage firms to displace competitors with only marginally better products – boosting private profits but adding little to overall welfare.

This trade-off occurs because firms tend to invest less in innovation when rapid imitation by competitors threatens to erode their competitive edge. An example of this could be a new type of battery. If companies can easily copy a technology once it has been discovered, then there is an underinvestment risk.

At the same time, if subsidies primarily support incremental innovations (like a battery improvement in the above example), they might fuel a cycle of firms displacing each other with only marginally better products, raising private profits but without generating much benefit for consumers or the economy.

These insights have significant implications for how we think about innovation and growth in GCR, particularly in shaping our innovation ecosystem, the Investment Zone programme, and maximising the opportunities offered by the Local Partnership Innovation Fund.

In terms of innovation policy, GCR needs to be strategic about R&D funding, making sure that our support flows to truly innovative ideas.

Strengthening the ecosystem would mean attracting and retaining talented people within the Region’s knowledge-intensive sectors – from Advanced Manufacturing and Life Sciences to Digital and Enabling technologies. GCR could also take advantage of wider shifts in global higher education by positioning its universities and research institutions as welcoming hubs for international researchers and innovators seeking supportive and collaborative environments.

The Region’s innovation strategy should begin within schools, colleges, and communities. Embedding innovation skills as well as digital and AI literacy across education, encouraging interdisciplinary problem-solving, and connecting young people with local innovators can help build a pipeline of future talent using emerging technologies.

Finally, there is a need to better understand why some high-growth industries perceive the UK, and at times Scotland, as a challenging place to operate, and to ensure that regional policies actively counter this trend.

Further Information

For queries and further information, please contact Christina Kopanou: